Reading Culture

I run into lots of people in Zambia who ask me what I'm doing here. It's a fair question, and so I tell them: I'm a librarian-in-training, conducting collection evaluation research in children’s libraries. And more than once now the person I'm talking to has looked at me with bemusement and a little bit of pity and said, "A librarian? But here we don't have a reading culture."

This is a hard idea to wrestle with on many levels. At its most basic, I struggle with the idea of reading as a "culture." Saying "we don't have a reading culture" seems a little like saying "we don't have an eating culture," or "we don't have a playing culture." These are basic activities that make up the fabric of a life, not culturally-specific traditions. Of course, what and how people like to read (or what and how people like to eat, or play) varies by culture, but the activities themselves stem from basic human needs. People need stories. People need information. Reading is certainly not the only way to get those things, but it is a direct, effective, and fulfilling way.

I read an article recently about the idea of “reading culture,” where Namibian professor Kingo Mchombu suggests that rather than lacking a reading culture many countries in Africa lack in terms of high-quality, relevant reading materials. This makes sense to me. How much of my love of reading is the product of instant gratification, of being able to always access the books I want to read? Between my library, ebooks, and local bookstores, I can’t think of the last time it took me more than an hour to get the exact book I wanted, or to find something even better. Would I still love reading if most of the books I had access to were outdated or so far removed from my life experiences that I couldn’t relate to them? As it is, I am a selfish, picky reader who finishes probably one in five of the books that I start.

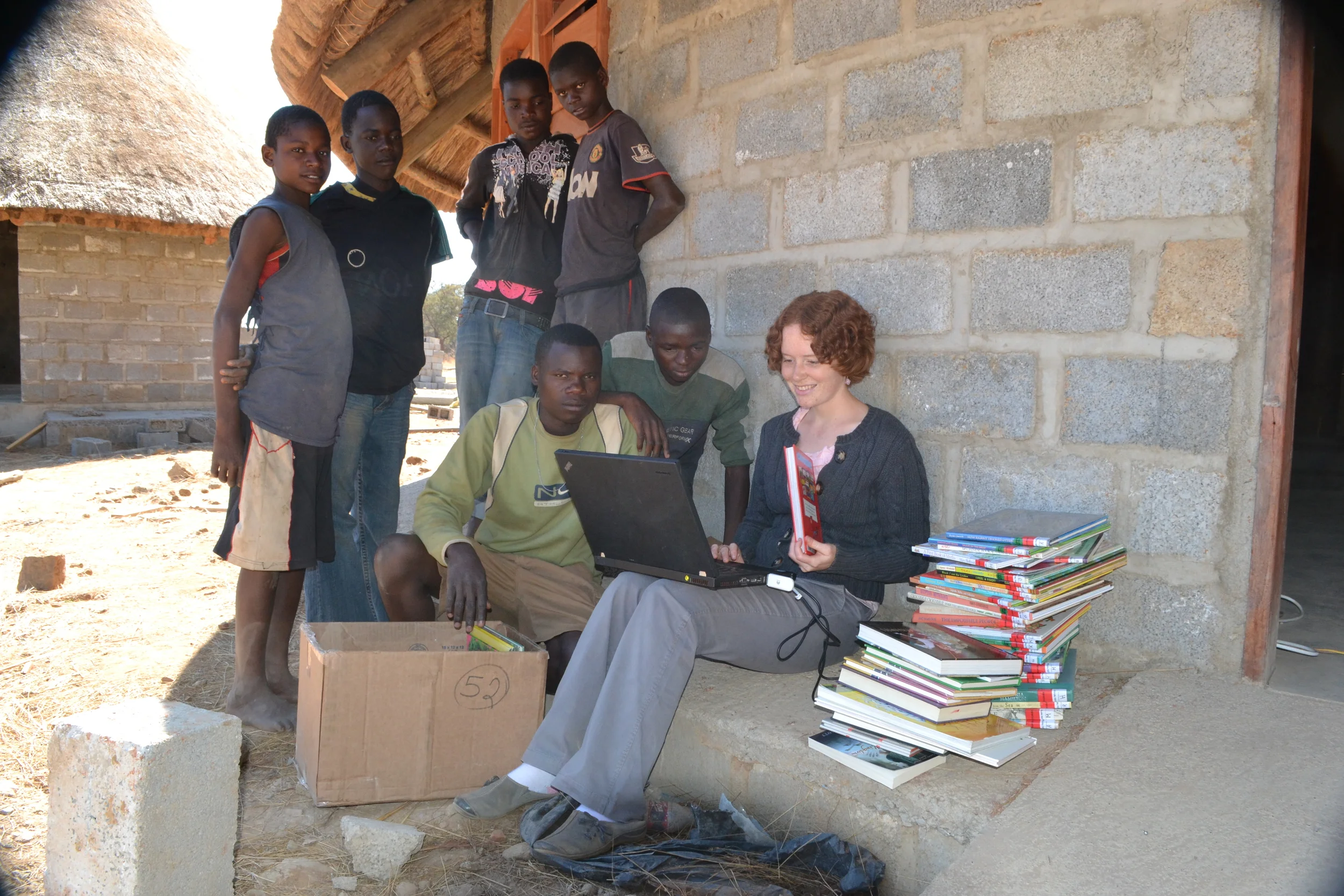

At the end of the day, though, Nabukuyu is the biggest indictment I have of the notion of “reading culture.” If you are trying to think of a place where access to books is limited, there is no better example. Nabukuyu is the very definition of rural—a village of widely-scattered homesteads 45 minutes from a small town via a dirt road. Most of the people who live there are pastoralists, and cattle are everywhere. Electricity, on the other hand, is only available three days a week. The school does not have a library, and I doubt there is a bookstore within a hundred miles. So you can see that to people who believe in the presence or absence of “reading cultures,” Nabukuyu wouldn’t offer many reasons to hope.

But I was privileged enough to be present this week when we opened the doors of the Mumuni library in Nabukuyu to children for the first time, and I can tell you beyond a shadow of a doubt that a vast majority children in Nabukuyu love to read. I can tell you this because of the incredible numbers of children who lined up outside, because of the expressions on their faces when they walked through the door—with eyes wide, mouths agape, like they had stumbled into Narnia— and because of how eagerly and excitedly they opened books and disappeared into them. I can tell you that children in Nabukuyu love to read because when I went to reshelve the mountains of books that had appeared in the baskets I didn’t have space to walk, the room was so full of children. I can tell you that children in Nabukuyu love to read because they brought their families: girls as young as six or seven came in with baby siblings on their backs and patiently arranged their wraps on

the floor of the talking circle as a playpen of sorts. I can tell you that the babies love to read board books or chew on them, at the very least.

I can tell you that children in Nabukuyu love to read because every storytime we did saw at least fifty children in attendance, requiring a great deal of patience as we spun in circles to make sure every single child got to see the pictures. I can tell you that children in Nabukyu love to read because the other day I walked past a boy on the road who greeted me by saying “chicka chicka boom boom” instead of hello, courtesy of the book I’d read for storytime the day before (“Chicka Chicka Boom Boom” by Bill Martin Jr.).

Last week you could have said that these children didn’t read, but you can’t say that anymore. And it’s for this reason—because I have personally witnessed how instantly and completely the provision of high-quality children’s books can create voracious readers—that I say with confidence that there is no such thing as the confusing, nebulous notion of a “reading culture.” The reality is achingly simple: If you give most children good, relevant books, they will like to read. They will get to the library early and peek in through the shutters while they wait for it to open. They will bring their friends. They will gasp audibly when they open a new book. They will come back again and again.